If our economy is built on growing consumption, then waste is not some unfortunate byproduct — it is the expected outcome. While there is reason to acknowledge the efforts made over the years, the released 2024 waste figures also reveal something deeper we need to reflect on.

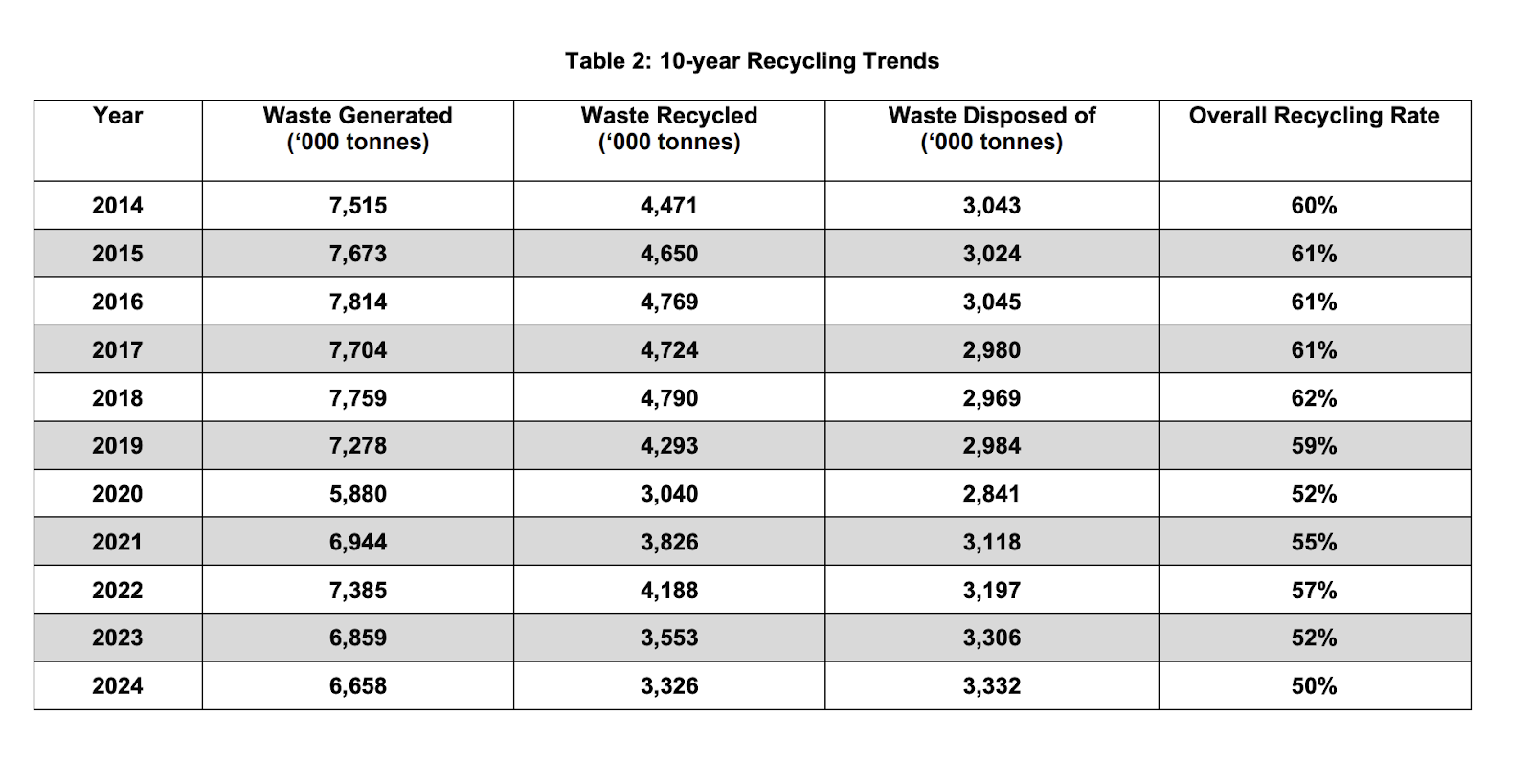

Total waste generated in 2024 has dipped slightly, which, on the surface, sounds promising. But looking at the data, the total amount of waste disposed of (third column) has actually increased. In other words, after all the sorting and recycling, we are still sending more waste to incineration and, eventually, to Semakau Landfill.

While recycling has helped minimise the amount to be incinerated, this trend is concerning, given that our goal is to slow the rate at which our only landfill fills up.

This may be an unpopular opinion, but I think it’s worth asking whether recycling of domestic waste should still be the foundation of our sustainability strategy. We spend a lot of effort measuring, tracking, and promoting recycling, yet much of our recycling model doesn’t align with Singapore’s constraints and capabilities. Singapore doesn’t have large-scale recycling infrastructure. Most materials are shipped overseas, but the economics of exporting low-grade recyclables are collapsing.

Recycling rates have dropped despite decades of campaigns. Dirty and overflowing bins discourage participation, especially in public housing where one blue bin serves an entire block. When we keep telling people to recycle—pooled together or sorted—we send the message that recycling is the default good deed, even if it’s not working. As a result, we overlook the importance of reusing or repairing and don’t question enough why the waste exists at all. Behavioural fatigue sets in when we keep pushing responsibility onto individuals without fixing systems.

If recycling in its current form is expensive, export-reliant, emotionally satisfying, but structurally weak, maybe we should not consider it one of our main metrics of success. And if we can agree on that, we should look to de-prioritise reporting on this front and emphasise minimising waste.

As a small island nation, we should not blindly follow recycling-based models that don’t fit our land use, economy, or values. After all, if countries with more resources and infrastructure struggle with domestic recycling, perhaps we need to take a step back and ask whether we should still follow suit. Instead, just as we did with our own water supply, what if we designed our own waste model?

We often rationalise that, as a small country with limited resources, we create our own unique solutions. Just as we addressed water challenges with NEWater and, concurrently, with newSand, we can focus our resources on building reuse models and ecosystems that work at scale—across events, F&B, retail, and households. Beyond recycling rates, here’s what I would like to see in waste reporting:

Recycling rates do not tell the whole story. If we want to nudge people towards reusing, we must start measuring and celebrating those numbers. I appreciate that it takes a lot of work, but if reduction and reuse data don’t even make it into the story, we will keep managing what doesn’t.

Even if these aren’t new data points, it would be helpful to improve how the data are shared:

I must admit that I don't envy the huge responsibility that the National Environment Agency has, and it’s the sheer scope—from trash to toilets to tombs (yes, it manages cremation too). It is not easy managing public hygiene, weather, cremation, waste, and environmental health—all while responding to a public that rarely thinks about waste until it becomes a problem.

Perhaps it’s not for lack of trying, but it might be timely to ask whether Singapore’s waste challenge now needs a more focused mandate that allows space for upstream thinking, innovation, and deeper cross-sector collaboration.

Just as smoke is the byproduct of fire, waste is the smoke of our growth-at-all-costs model. More fast food outlets, bubble tea shops, and food delivery services will surely create more disposable waste. As a society, we should not be surprised when our waste (recyclable or not) keeps increasing, even as we run more awareness campaigns or introduce more recycling bins.

Let’s reframe Singapore’s waste story by being honest about what’s working and what needs to change.

Get the latest news from Green Nudge

Green Views

Aug 25, 2025

5 min

read

If our economy is built on growing consumption, then waste is not some unfortunate byproduct — it is the expected outcome. While there is reason to acknowledge the efforts made over the years, the released 2024 waste figures by National Environment Agency also reveal something deeper we need to reflect on.

Green Views

Aug 5, 2025

5 min

read

In recent times where efficiency is prioritised and often seen as the default, what does it really mean to be useful? What do we lose when we discard the ‘inconvenient’ in a culture that values speed and optimisation? At Green Nudge, we talk a lot about sustainability for the planet. But increasingly, perhaps the harder (and more important) conversation is about where that intersects with relationships — how we stay in connection so the change we want to see can truly last.

Green Views

June 3, 2025

7 min

read

Singapore recently concluded another round of general elections. We showed up, queued, verified our identity, and were handed a small slip of paper to mark our vote and drop into a ballot box. In a world where almost everything has gone digital — from banking to paying for drinks — why are we still voting with paper and what’s the environmental cost of doing so?